Estimated reading time: 13 minutes

Just hearing the words “fruit fly” is enough to strike fear into the hearts of many fruit growers. It’s one of the pests that make people want to give up fruit growing altogether.

We’re here to change your fear into calm confidence!

Identifying fruit flies

If you live in an area where they’re common, you may already have experienced how much damage they can do. If you’ve never experienced them before, you’ve probably heard horror stories.

There are actually many different species of fruit fly. Of them, about 10 species are known to be pests of fruit. In Australia, Queensland Fruit Fly (QFF) and Mediterranean Fruit Fly (MedFly) are bad pests.

QFF is the one that’s of particular concern to home fruit growers.

Learning about fruit fly from the expert

We’re always trying to learn more about fruit tree pests and diseases and regularly go to workshops. We were so impressed by a workshop given by fruit fly expert Andrew Jessup (sponsored by Mount Alexander Shire Council) that we asked him to present a Masterclass for our Grow Great Fruit community.

Luckily, he agreed.

It was fantastic! Andrew has a knack for making the lifecycle of the flies interesting and even relatable. You can watch the masterclass here.

The class goes for about 2 hours and is very informative and entertaining. However, if you don’t have time to watch the whole thing, we’ve summarised the main points in this blog.

Why is fruit fly such a bad pest?

QFF is a very successful insect. In fact, it is one of the most adaptive insects known. It functions in new environments and adapts to new fruits very well.

Another thing in its favour is the fact that it lays lots of eggs. A single mating leads to 2,000 eggs, and a high percentage go on to become adults.

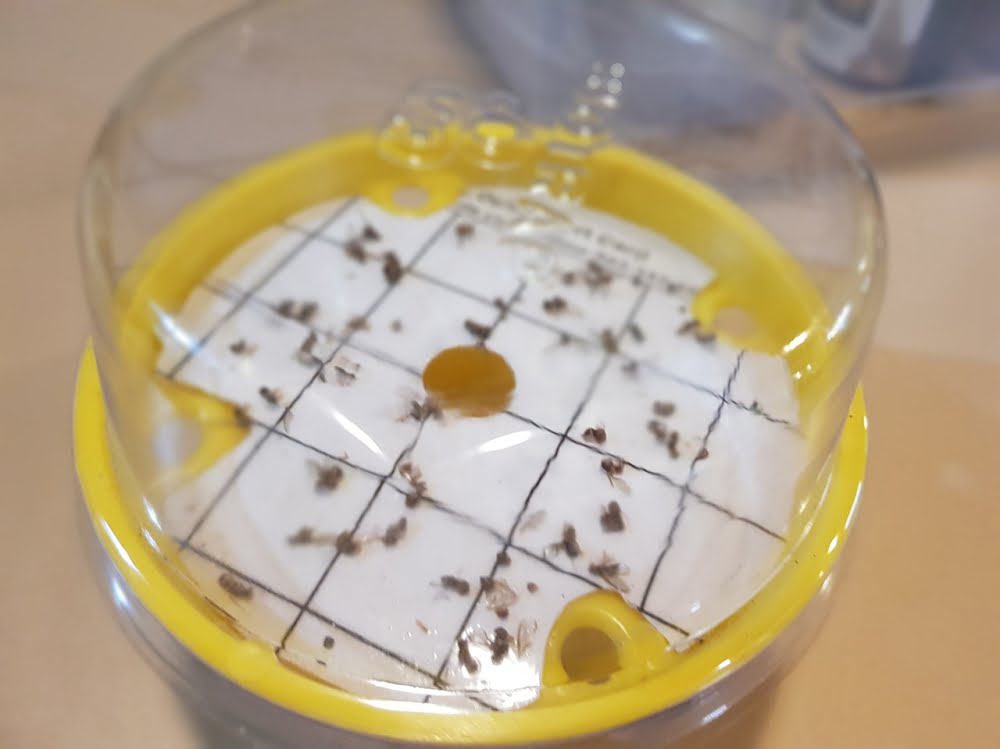

QFF is just one of many different types of flies, and many of them can get caught in traps. Just because you’ve caught something in a trap doesn’t mean it’s QFF. It’s important to get a positive ID.

Everything you wanted to know (but were afraid to ask) about fruit fly sex lives

Fruit flies only mate at sunset, and only on days when the temperature at sunset is over 16C. In a time-honoured tradition, the males gather together, sing, and put out a cloud of pheromones.

The males can mate many times, but the females usually only mate once – unless it’s not successful the first time. After mating the male gives the female a ‘nuptial gift’ of a protein parcel. This helps her to fertilise and lay the eggs.

On a side note, one of the unintended consequences of the sterile fruit fly release experiment being trialed in parts of Australia is that the sterilised flies are less likely to deliver this nuptial gift. As a result, many of the females that have mated with sterile males go in search of wild males and re-mate.

Do fruit flies survive over winter?

At the end of summer, any flies that are still alive will look for somewhere to try to survive the colder months. Eggs, larvae, and pupae are very intolerant to the cold and will die. Mature flies can live for up to 4 or 5 months through the winter. Their metabolism slows down if they can find a warm spot to shelter, and this helps them survive.

They tend to congregate in warmer places such as evergreen trees (e.g. citrus). Even in very cold temperatures and frosts, evergreen trees will retain some warm patches within the leaf canopy. This warmer air provides protection for overwintering adults. Most of the winter the flies won’t be moving around much unless daytime temperatures warm up to more than 12C.

Other warm spots near houses like hot water systems may also provide protection. These aren’t the fruit fly hideout of choice though, because they don’t provide any protection from predators. They prefer more secure places like chook pens. These spaces tend to be warm and give off the scent of ammonia which attracts the flies.

Can you kill or trap flies in winter?

After hatching, flies are not sexually mature at the start. They need to find protein, and this is also true of flies in winter. Therefore you can put protein baits or female-biased traps in potential over-wintering spots. In winter their metabolism slows down and they’re more interested in eating than sex.

Don’t bother putting out male traps in winter because they’re really not interested in sex.

These protein bait traps don’t pull flies in from a long distance. You’ll need to put one in every tree or potential hiding spot. The flies smell the protein and are attracted to it. The traps also contain a poison to kill the flies, and may also include something sweet to encourage them to the bait.

Common garden features that can help beat fruit fly

Chickens are one of the best defenses against QFF, and only need to be active during the day as this is the only time the fruit fly larvae will be actively coming out of the ground.

Broadleaf weeds provide an excellent resting space for fruit flies, so it’s a good idea to keep them mowed and short. Mulch also provides a perfect place for fruit flies to pupate.

In Victoria, fruit flies have been in East Gippsland for more than 100 years, and Melbourne suburbs Ascot Vale and Moonee Ponds are riddled with QFF. Why does this matter? Because controlling fruit flies in urban regions helps rural areas. Flies move from urban to peri-urban regions, and then to orchards.

What’s the best way to prevent fruit flies?

Step 1 – Monitoring

Put out monitoring traps to detect males early in the season before the sunset temps reach 16C. They contain pheromone lures, so theoretically 90% of the catch will be QFF (not other types of fruit fly). These traps attract flies from up to 300-400m away.

The lure lasts for about 4 months after you put it out, but you can buy replacement lures, so don’t throw the trap out at the end of the season because they’re reusable. (Pro tip: write the date on the side of the trap in permanent marker the day you put it out.)

Step 2 – Identification

if you catch one, make sure you get a positive ID. Here in Harcourt, we’re lucky enough to have an Emergency Outbreak Plan (EOP), so a positive identification of a QFF will trigger the EOP being put into place.

If you don’t have an EOP and your community is at risk from QFF, ask your local council to prepare one (use the Harcourt one as a template). Alternatively, check out our Free QFF Resource Pack for more response ideas.

What’s the best fruit fly trap?

- it’s better to have a yellow base and a clear lid, rather than the other way around. If they land on the lid and can’t easily get into the trap they fly away, as they prefer being under things than on top;

- check the concentration of lure in the trap. It needs a minimum of 2g per lure to work properly;

- sticky traps catch everything because they don’t use a pheromone to attract the flies. They use a fruit smell as the lure, and this attracts a wide range of flies and insects including bees. They also don’t work as well because they’re competing with other fruit smells, and they only attract flies from about a 15m radius;

- protein traps also attract other types of insects. It’s best to put this type of trap out if your monitoring indicates that QFF is present. Put them out at least 6 weeks prior to harvest. Don’t put them in fruiting trees, but in the tops of lemon trees is OK because lemons are not a major host of QFF. This is particularly true of the Eureka or Lisbon varieties, though fruit fly don’t mind the sweeter lemons like Meyer and Lemonade;

- home-made traps have limitations. They attract all types of insects, so you can accidentally be killing beneficial insects. In addition, they will often only work for 2-3 days;

- Don’t leave protein-based traps (home-made or commercial) in the hot sun. High temperatures will denature the proteins and make the trap ineffective;

- place traps on the north-eastern aspect of the tree as this is where the flies are most likely to be active in the morning.

What fruits do fruit flies prefer?

This is a great question, and of much interest to home fruit growers hoping their trees will be exempt!

Unfortunately, fruit flies are very opportunistic. This list includes their favourite fruits, but in fact, they’ll lay eggs in the best food source available, even if it’s not on the list.

- Feijoa

- Guava

- Loquat – the perfect fruit for them at the beginning of the season because they ripen so early

- Berries

- Cherries

- Almonds

- Vegetables: tomato (cherry tomatoes and Roma are slightly resistant as they seem to have more slippery skins), red chilies, and red capsicum are some of their preferred veggies.

Which fruit don’t fruit flies like?

- Lemons, especially the sour lemons like Eureka and Lisbon (but being opportunistic little buggers, they’ll even infect lemons if none of their preferred fruit is available);

- Pistachios

- Grapes

- Walnuts

- Olives

- Avocados – they won’t attack them on the tree, especially Hass, though they’ll attempt to get through the skin if they’re short of better options. This (or Fruit Spotting Bug) is one of the causes of the small hard masses you sometimes find in avocados.

- Purple passionfruit

- Persimmon – the astringent types, but they will attack non-astringent ones

In America, growers spray Giberellic acid onto citrus trees to try to make the skin harder to give resistance to fruit flies. This is not a common technique in Australia.

Hot hurricane-type winds can blow QFF very long distances, but in windy conditions, they’ll often just hunker down and hang on in the tree they’re in. Very hot conditions (especially dry heat) will also make them stay relatively immobile in a cool spot in a tree.

Preventing fruit flies from getting to your fruit

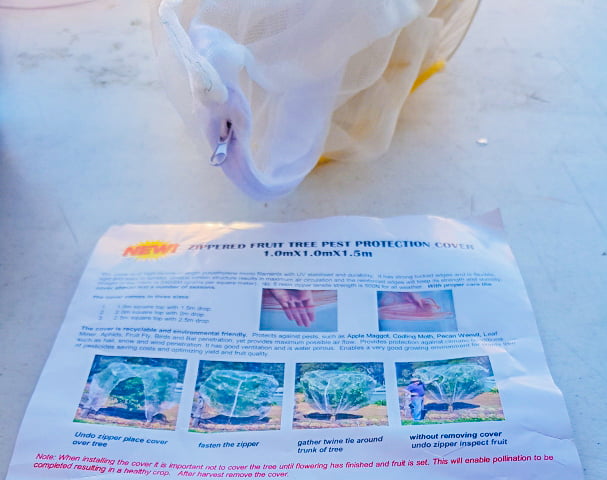

The most effective anti-fruit fly technique is netting, without a doubt.

The netting needs to be a maximum of 1.3 mm hole size to prevent the flies from getting through. They can still sting any fruit that is next to the net, so it’s not a perfect solution. However it’s still one of the best lines of defense, so if you need some help with figuring out the logistics of setting up your netting system, download this short course.

Like most things to do with fruit growing, netting can also have unintended negative consequences. It can cause an increase in humidity that can actually provide better habitat for other pests.

Bagging your fruit

Bagging individual fruit or branches is more reliable and in some cases simpler than netting whole trees. For example, some people use white, waxy paper bags. Either cut the base out or put a hole in the bottom of the bag to allow drainage of condensation and then tie the bag around the fruit. It’s time-consuming but effective.

In the Pacific Islands, growers use wet newspapers to protect the fruit. They fold it around the fruit like a nappy. When the paper gets wet it turns into a type of papier-mache that somehow remains intact and lasts for the entire season.

Does companion planting work?

There’s no good hard evidence for this. Plants like artemis, marigolds, mint, and wormwood (and other strong-smelling herbs that would have been used in Mediaeval times as ‘strewing herbs’) are reputed to repel fruit flies.

If you’re using this strategy, let the plants grow under your fruit trees, then slash them and let them lie on the ground.

What eats fruit flies?

QFF has many natural predators, including:

- Robber fly

- Assassin bug

- Jumping spiders

- Parasitoid wasps (but only if the fruit is already infected)

Like all pests, it’s futile trying to completely eradicate the pest population.

The only way you can attempt this is with chemicals. This might reduce the population for a while, but the pest inevitably comes back.

Fruit growers who rely on chemical control of any pest find themselves having to constantly spray for the same pest. In fact, they may be accidentally making the problem worse by killing the very predator insects that would be eating the fruit flies.

Pesticides that are commonly used to kill fruit flies (and other pests) also run the risk of harming human health and damaging the environment. It’s much better all-around to go the organic route.

What’s the best way to attract predator insects?

As well as the monitoring and protection mechanisms discussed above, the QFF population will have much more trouble building up to problematic levels if your garden is bird-friendly, attracts many different types of insects, and is home to a few chickens.

Related Articles

6 step plan for beating Codling moth in apples

The classic “worm in the apple” is actually the larvae of the Codling moth, a very annoying pest that needs a planned effort to prevent.

What You Need to Know About Pesticides

Growing organic fruit has never been so important, with new evidence showing pesticides escaping into the environment at scarily high rates.

How to overcome fear of insects in fruit trees

Are insects in fruit trees a bad thing or a good thing? Learning to appreciate insects is an important part of adopting an organic mindset.

Does it matter what the colour of the base of the FF trap if the cover is clear?

Hi Morrie, most traps are yellow because that seems to be the best colour to attract insects.

Insects are attracted to yellow…hence centre of flowers yellow etc…

Very true Chris, it always pays to watch what’s going on in nature!

Do you know if they attack the hardy thick skinned bush Lemon?

Where do you get traps from?

How long is the life cycle of QFF? Does it last for one season or multiple generations of them in a season?

Unfortunately they have a short lifecycle, and can go through multiple generations in a single season Amir – that’s one of the reasons they’re so successful.

Are ducks also good, or only chickens?

Regarding pheromone traps – do they only attract QFF or a range of flies? Also, I believe some traps attract just the males, while others attract both males and females. Which is the most effective? Thanks!

The bought traps with pheromones attract mostly QFF – either males or females depending on the type of trap, you’re right Roslyn. The home-made traps attract other insects as well. The male and female traps are effective in different situations, but the male ones are recommended for the monitoring phase. If you haven’t checked out our QFF Masterclass yet, the different types of traps and when to use them is one of the things that our QFF expert Andrew goes into at some length – https://growgreatfruit.com/product/queensland-fruit-fly-masterclass/ (it’s a really fantastic masterclass). We also have a free Fruit Fly resource you can download from the website that talks about the different types of traps as well. You’ll find that here

– https://growgreatfruit.com/product/queensland-fruit-fly-resource-pack-free/

Hi guys, are you able to tell me where to get bio traps from? I’ve contacted them directly with no response and can’t find a supplier anywhere?