Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

We’ve been interested in the possibility of using biochar with fruit trees since we went to a workshop on the topic, way back in 2017.

It was one of those mind-blowing moments in our learning journey that opened our eyes to the full awesomeness of the stuff.

We’ve since learned these two backyard methods for making biochar, and even how to make biochar in a bathtub. We’re keen to spread the word about this magical soil amendment.

There’s nothing new about biochar

At our very first workshop, we learned about biochar from one of Australia’s leading biochar experts, John Sanderson from Earth Systems (on the left, below).

He was joined by his colleague Lann Falconer. The workshop was held on a gorgeous day in the beautiful Growing Abundance Hub Plot Garden.

Most gardeners have heard of biochar, even if not a lot of people are making or using it (yet!). However, John made the point that biochar (as we know it now) is not a new soil amendment.

It’s been used for thousands of years by many cultures around the world.

The most famous is the ‘Tera Preta’ soils discovered in South America. Similar types of soils have been found throughout Africa and other places, where biochar is actively used as a soil amendment to this day.

Despite some good early work on biochar in Australia, much of the activity has shifted elsewhere. Europe and California have become the hubs for biochar research. This is due to difficulties in attracting research funding and finding markets in Australia.

Considering Australia’s arid environment and propensity to drought, we reckon that’s a missed opportunity. Could biochar help you to keep your fruit trees healthier in a drought?

Biochar is mainly made of holes

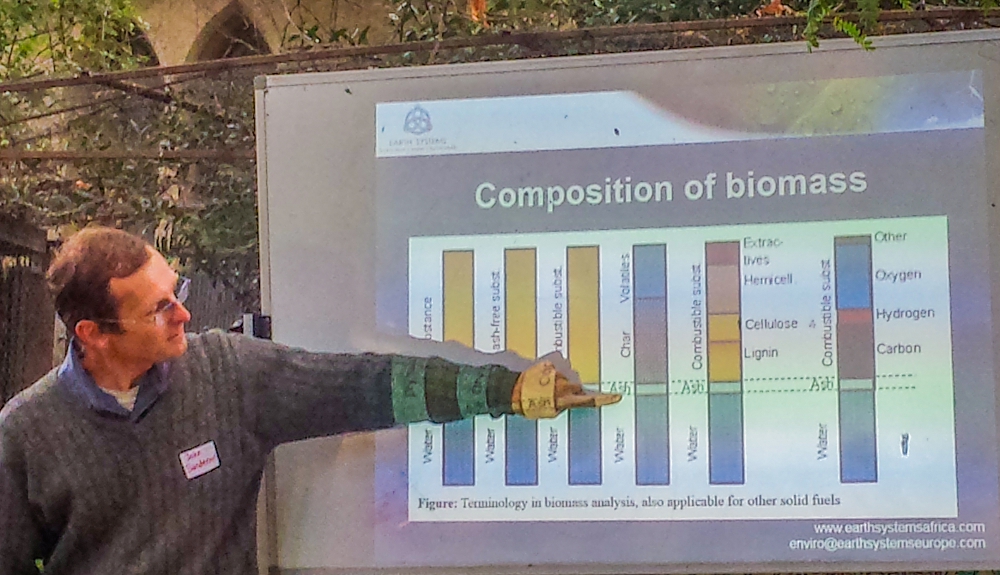

While biochar is similar to charcoal, it’s a bit different, mainly because of the temperature.

The perfect range for producing biochar is 350°C–750°C, higher than charcoal. If you make it at a higher temperature you lose some of the properties that help make it so useful in the soil. If produced at lower temperatures it will still contain volatiles that may have a detrimental effect on the soil.

One of the amazing properties of biochar is its incredibly large surface area, from 500 to 600 square metres per gram.

If you look at biochar under a microscope, it’s full of holes. The holes are full of holes, which are full of more holes (called micropores). In fact, there are more holes than matter!

This is what gives biochar its incredibly large surface area. It’s also what makes it ideal for both holding water and providing the perfect habitat for soil microrganisms—it’s basically like an empty block of flats for microbes!

Biochar is so good at holding on to moisture that it could be a game-changer for Australian soils. Just 4% in sandy soil doubles the amount of water that the soil can hold.

Impacting climate change with biochar

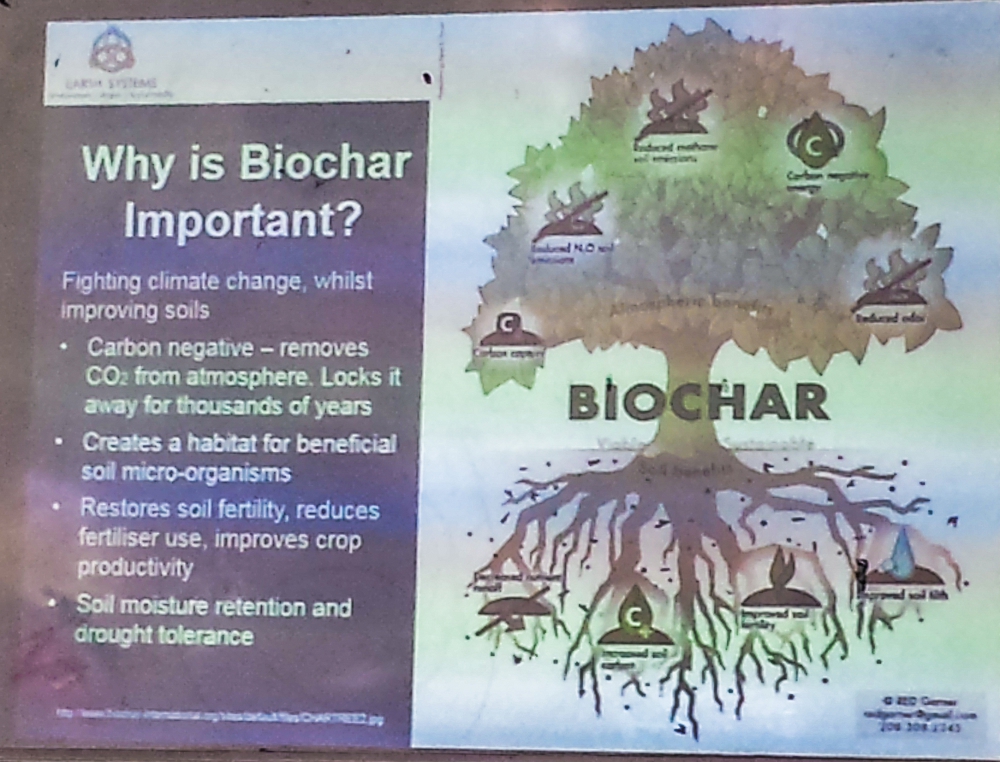

Growing fruit trees is a very practical way to help reduce climate change. You’ll be pleased to hear that adding biochar to your fruit trees can increase your impact.

Making biochar dramatically reduces the amount of greenhouse gas that is released into the atmosphere if it’s made from stuff that would otherwise rot, go to the tip, or be burnt.

When biomass is turned into biochar, approximately 50% of the carbon is burned off. The other 50% is turned into a highly stable form of carbon, which will last for at least 1,000 years in the soil.

For every ton of biochar, this represents 3.6 tons of CO2 sequestered (i.e. put into the soil). And it stays there for a long time.

But how much difference can it really make?

John reckons that if we could fill up three open-cut mines with biochar, we’d be about halfway back to when we took the coal out of the ground.

Biochar can also decrease emissions of nitrous oxide, which is another potent greenhouse gas. However, the mechanism is not yet understood. There have even been some situations where biochar application has made emissions worse, e.g., with the use of nitrogen fertilisers in dryland agriculture.

How biochar improves soil fertility

Before the workshop, we knew that using biochar with your fruit trees makes the soil much more fertile. Afterward, we also understand why.

It’s because of its awesome ability to hold nutrients and prevent them from being leached away.

It can get a bit technical, but when used in your garden, biochar has a positive effect in several ways. It can have a physical impact, affect how water is stored, and also have chemical and biological impacts.

Physical

This is because of the vascular nature of the source material.

Hydrological

Biochar dramatically increases the water-holding capacity of the soil because of the huge surface area and micropores.

Chemical

The inoculation process (see below) puts nutrients into the biochar before you use it.

Science alert: the next bit gets a bit complicated, but if you like to understand what’s really happening in your soil then read on.

Biochar is made of carbon, which is the chemical backbone of all life. Biochar can carry oxidised groups such as phenolic groups (charge of -1) and coboxyls (charge of –2), which are anions and like to bond to cations such as calcium (Ca, charge +2), magnesium (Mg, charge +2), potassium (K, charge +1) and ammonium nitrogen (NH4, charge +1). These cations can be released to plants in exchange for hydrogen ions (H, charge +1), and thus act as a store of these cations needed by plants, reducing the loss of nutrients from leaching and thus reducing the need for added fertiliser.

Got it? Good!

Biological

Between 4% and 6% of biochar is biological carbon. Microbes can eat this carbon, and biochar is also the perfect microbial habitat. Biochar can encourage enzymatic processes. It also attracts fungal inoculation, which can happen even if biochar is out of the soil.

Activating biochar

This is an industrial process that further erodes the biochar until more of the walls are gone and it becomes like coral. The process involves using oxygen, steam and high temperatures. It can increase the surface area even more, up to 2,000 square metres per gram.

Activation only works if the biochar was originally made out of something very hard like coconut shells, If it’s made out of something soft, activation makes the biochar fall apart.

How to make biochar for your fruit trees in a milo tin

You can make biochar by applying heat to any plant material (like fruit tree prunings) in a low-air environment.

First, the water boils out. If you were burning in the air (and not a closed container) the material would burn next. But because you’re doing it with less air present, the volatile gases are given off.

This smoke is acidic, and it’s important to make sure it’s burnt in the process of making your biochar.

When it’s made industrially, the smoke can be condensed and collected. Then it’s called either wood vinegar or smoke water. Though it’s acidic, it’s also very nutritious and has various uses.

The technical term for a sealed container for making biochar is a “retort”. At the workshop, John demonstrated a simple homemade retort made from a Milo tin with holes in the bottom that sat on a gas burner. It made biochar in about 20 minutes and really demystified the process.

You’ll often find biochar at the bottom of your wood fire, which is the wood that didn’t burn because air couldn’t get into all of it.

There are lots of different ways to make biochar, including in a bathtub or a 44-gallon drum. Whatever system you set up, the aim is to heat the stuff as little as possible.

However, it’s important to have enough air to burn the volatiles, or you generate massive amounts of horrible smoke. The most important thing is to NOT make smoke, there should only be a heat haze.

What can biochar be made from?

Biochar can be made from a wide range of source materials. Moisture content is not relevant, but the drier it is, the easier it is to light and to keep burning.

- Fruit tree prunings.

- Soft wood like pine or cypress makes good biochar, but the wood vinegar is no good.

- Sawdust is excellent.

- Treated timber (ex-building) contaminated with creosote is OK. The creosote is burnt off in the thermal process and leaves no residue.

- Garden clippings or prunings.

- Any plant material.

There are some things you should not make biochar from:

- Timber that’s been treated with chlorine-based chemicals should NOT be used because the heat process creates dioxins which form a toxic emission, e.g., railway sleepers have been treated with dieldrin which creates toxic dioxins.

- If wood has been treated with copper or chromium, for example, this should also not be used because it creates contaminated biochar.

- Rotten, light, or spongy wood is not as good because it has lost its structure.

- Wood that’s painted with lead paint.

A typical fuel that works well is garden pruning waste about finger thickness. This burns about 25mm per hour, so wood with a diameter of 150mm will take about 6 hours to turn into biochar.

If you use smaller fuel, the process is faster, but you have to weigh up the energy and time involved in reducing the size of the fuel with the energy and time involved in the burning process.

An easy home method (a scaled-up version of the Milo tin)

- 205 litre drum

- Tight lid

- Holes in the bottom. Start with small holes, because you can make them bigger. Recommended: 12 mm holes in a complete ring at 25mm spacing, and another 10 or so holes in the middle (this has worked well). If there are too many holes the biochar will burn and you’ll end up entirely with ash. Too few holes and you may overpressure the system, which will lead to the drum distorting (it’s unlikely to explode). Smoke goes out the bottom through the fire, so the volatiles are burned.

Keep stoking the fire under the drum until it’s all turned into biochar. You can’t tell until you open it, so notice the diameter of the wood as it goes in and use that to guide you.

There’s no need for a temperature gauge, but you can use one, particularly if using large pieces of wood. Drill into the middle of the largest and put the probe in, and burn until it reaches 500°C—that should make sure it’s finished.

Caution: the process can produce carbon monoxide and so should never be done in a closed environment.

Toplift Pyrolyser Method

This is a great technique for using fine material like sawdust.

Use a drum that is packed in a uniform fashion (like making a cigarette), and light the material at the top. It’s a good technique if you have a fine source material, as it burns uniformly down from the top and no air gets in so there’s no ash, just charcoal.

Once biochar is made it needs to be crushed, and a small mulcher is perfect for the job. The finer the better, about 3-5 mm is ideal, or slightly larger (10-20 mm) if you’re using it in potting mix.

Inoculating biochar

Biochar must be ‘charged’ or inoculated before you apply it under your fruit trees. Otherwise, it will suck water and nutrients out of the soil to fill all the pores in the biochar, which can shock your trees.

So before use, biochar must be filled with water, nutrients, and microbes. Once it’s charged you can safely add it to the soil. Then the water and nutrients become available for the plants, and the magic can begin.

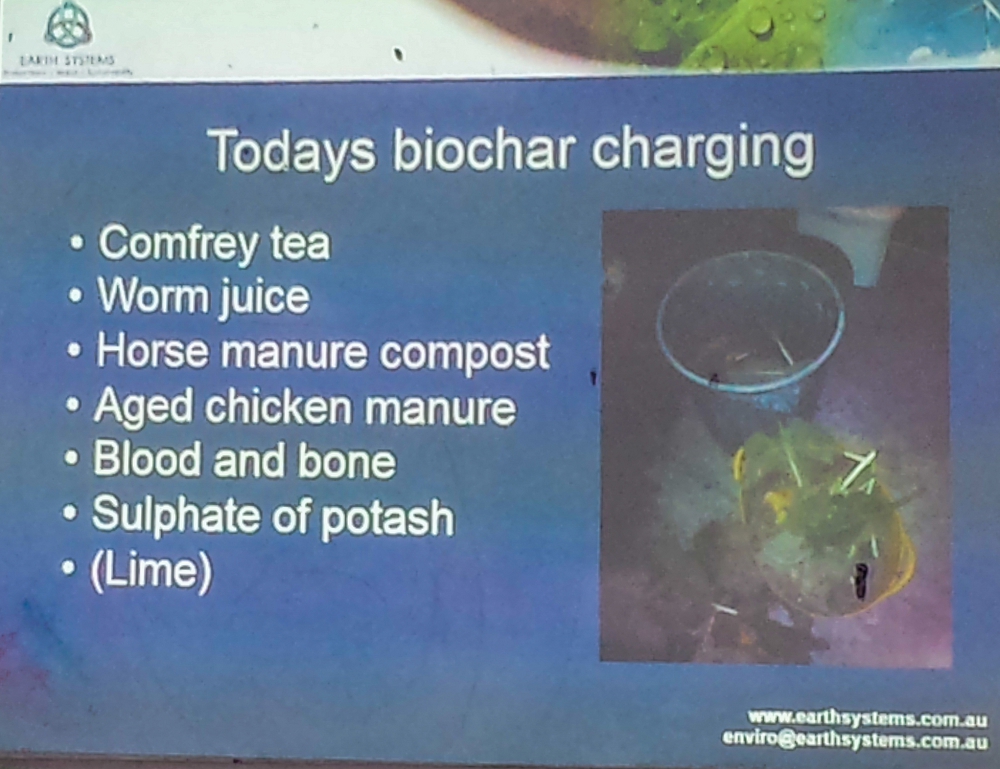

When inoculating, try to mix up a complex blend. It’s best to use a diversity of products from lots of different sources.

An easy way to inoculate the biochar is to keep it near your compost bin. Simply add a couple of handfuls of biochar to the bin every time you add scraps. The right ratio is about 1 cup of biochar to a small bucket of food scraps.

You can also add biochar to a worm farm, as worms LOVE biochar. One of the tests performed to test any new soil amendment is called the Worm Avoidance Test. When biochar was tested in this way the worms flocked towards it. It has the worm tick of approval!

What to use for inoculation

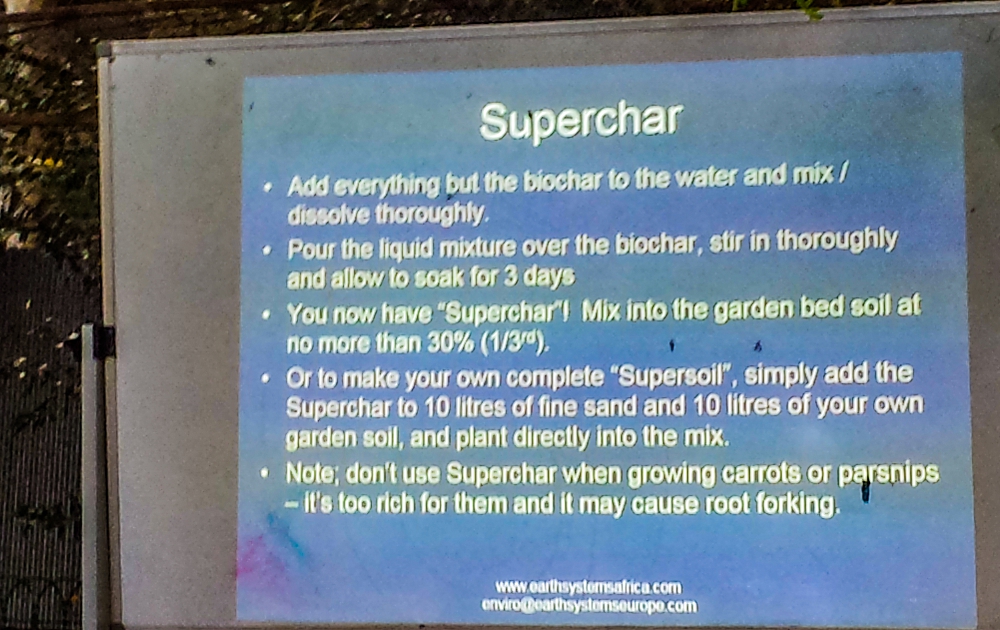

Mix up your choice of inoculants from the following list, or the ingredients listed on the slide above.

- Worm juice.

- Compost tea or compost extract.

- Comfrey tea—is high in phosphorus and potassium. Make by soaking comfrey in water for 20 days, turn a few times. It stinks but is brilliant.

- Wood vinegar—has lots of nutrients, but is optional.

- Water-soluble trace elements, e.g., Thrive.

- Aged manures.

- Compost.

- Limebiochar—has a slightly alkalizing effect because it contains the positively charged minerals that were in the original plant matter, and usually has a pH of 8.0–8.5.

Mix with your biochar and leave to sit for a week or two before applying it. Cover completely with water to prevent mosquitos from breeding in it.

Biochar plus worm tea or a complex of ingredients is the equivalent of creating rocket fuel for soil!

How to use biochar

We’re mainly interested in using biochar with fruit trees. However it’s useful for most plants in your garden, and also has a number of other uses.

It’s best to incorporate the biochar into the soil. If you leave it sitting on the surface it can actually increase the temperature of the soil because it’s pure black.

Here are some practical suggestions:

- Add 10%-20% in wicking beds. Smaller amounts will still be useful. It can be incorporated into a new bed (in which case it’s fine to use up to 40% biochar) or added to an existing bed.

- Apply to the root zone of your fruit trees. This is particularly useful in helping establish mycorrhizal fungi in the rootzone.

- Supercharged biochar will act as a slow-release fertiliser, and smaller amounts (e.g. 5%) are useful.

- Add to homemade potting mix. It makes a more porous mix that resists compression and is great for indoor plants.

- Feed to your animals. About 80% of the biochar produced in Europe is fed to animals. It’s great for their gut and means they belch and fart less.

Other uses

- Broadscale farming,e.g. wheat crops in California.

- Biochar is really good to help clean up chemical spills.

- Biochar can be eaten by people and is good for human gut health!

Biochar is without a doubt an exciting new (old) aid to growing healthy fruit trees.

But we completely understand that the idea of setting up a whole new system to make it can feel daunting.

John finished the workshop by mentioning that it’s completely fine to use biochar from your fireplace or bonfire. That surely makes it feel a bit more achievable!

Related Articles

Fruit tree leaves: bonus or problem?

Should you let the leaves from your fruit tree stay on the ground in autumn, or are you just asking for trouble? We’ll help you decide.

Should you spray your fruit trees in autumn?

Spraying fruit trees should always be kept to a minimum to protect soil health, but sometimes a spray in autumn is the right thing to do.

How to plant a green manure crop

Prepare the soil before planting fruit trees with an autumn green manure crop, and give your fruit trees the best possible chance to thrive.

Great article. I’ve had a go at making biochar, I think I ended up with charcoal rather than biochar but I’ll keep trying.

Wow I have never heard of Biochar, thanks for sharing, I’m off to Bunnings to buy some

Glad it’s piqued your interest – check out Tania’s idea above for a simple DIY option! Cheers – Meg, GGF team.

Love this article. Thank you.

I use tins filled with wood chips in my wood heater to make biochar. It means I don’t have to waste extra fuel to make it and the volatiles are burnt off easily.

Great idea Tania! Thanks for sharing – Meg GGF team.

As a new member I’ve just read this post for the first time. I have been practicing the use of biochar since I planted my mini orchard in the backyard of my house in the far southwest capes region of WA. The more I study biochar the more I understand why my trees are so proficient in delivering nutrient dense fruit. One of the less recognised attributes of biochar and its microscopic porosity is that it slows down Nitrifying Bacteria and enzymes from converting atmospheric nitrogen to nitrate. The benefit of the slowdown is that nitrate takes a lot of water to translocate within a plant, and this significant volume of water dilutes all the other essential elements travelling in the solute with nitrate. When the ammonium nitrogen is loaded into the biochar nano-pores, the bacteria and enzymes no longer get unrestricted access to undertake the conversion, which means all the essential elements will be translocated in solutes of the correct viscosity……and that brings maximum benefit to the plant.