It’s completely fascinating seeing the rich tapestry of rice paddies, ducks, cows, water buffalo, aquaculture, corn fields, orchards, vegetable plots, jungle, chickens and various mystery crops – and of course houses, villages, and tombs dotted throughout the landscape, that fills pretty much every inch of the countryside between cities.

Our heads are full of dozens of questions, making us acutely aware of how little we know about farming outside our own specialty and climate: are all those people in the rice paddies weeding, planting or harvesting? Do they own the land, or do they work for someone else? How on earth do they get the water to move exactly where they want it in such a flat landscape (there’s a huge amount of water, at different depths in different paddies, and we can’t see any pumps or infrastructure)? What are those trees (we ask ourselves that question a lot)? Why are some cows tethered and others seem to roam free? Why are there fences in some areas but not in others – is it all one big farm or lots of little ones cheek by jowl? Are those things that look like haystacks actually haystacks, and if so what’s the crop and what are they used for (and how on earth do they get them so high?)

Whenever we’re lucky enough to find a local that speaks enough English we pepper them with questions, learning a bit more each time. (We speak only about ten words of Vietnamese, enough to order a beer but not enough to ask anything at all about farming.)

We’ve become very aware of the double-edged sword that tourism represents, as are many of the locals we spoke to. This region used to be very poor, and some of the locals working at Phong Nha Farmstay have memories of hungry childhoods and extreme poverty, even Hung, a supervisor at the farmstay, whose father is the head man of his village.

The district around Phong Nha is now experiencing a huge tourist boom, largely due to the caves which receive an average of 3,000 visitors a day! It’s providing heaps of local employment and helping to lift the region out of poverty. Much of the wealth going into local communities seems to be put immediately into improved housing, and we saw prosperous-looking houses being built everywhere, much of it replacing simple wooden shacks that people lived in previously.

The development of rural tourism is also providing an alternative to the trend of young people leaving rural districts to find work in the big cities so they can send money home to support their families. After experiencing life in a large, modern, cosmopolitan city, many don’t then want to return to take over the family farm when the time comes. However, most of the young people employed at Phong Nha Farmstay are from the local area, and it’s providing them with the means to stay. While we there, Huong, one of the bar staff, was looking a bit bleary-eyed for a day or two because it was corn harvest season, and she was rushing home from work to help with the family corn harvest, which extended well into the nights until it was all finished. Though university educated (nearly every young person we’ve spoken to is), Huong plans to continue both her career in tourism and the family farming tradition.

The downside of this economic boom is the same as it always is – loss of cultural identity, changes to traditional family life, big business moving in, and destruction of natural resources. We were pleasantly surprised at how sensitively the Vietnamese government seems to be developing the cave region, but 3,000 visitors a day takes its toll nonetheless, and while the locals welcome the new opportunities that are opening up, several also mentioned aspects they find distressing.

Change is always difficult, and it’s easy to form quick judgements about whether something is “good” or “bad” through our priveleged western eyes. Meeting Cuong gave us more food for thought.

Cuong is a young farmer with a very entrepreneurial glint in his eye! He can see the opportunity created by the flood of tourists to his district, and is keen to grab the chance with both hands so he can raise his family out of subsistence farming, give his kids a good education, and employ people to do his farm work! He’s working on creating a farm tourism experience for foreign visitors (despite the huge rise in domestic tourism Cuong isn’t aiming for this market, as he thinks they are too demanding and leave too much rubbish around!).

We were the first visitors to take up his offer of a farm tour, and he couldn’t quite believe we really wanted to see it, thinking it a very poor example compared to the huge and pristine farm he seemed to imagine we had (if only he knew!). It was fascinating, and we really valued the chance to see it close up and ask loads of questions. We had to resort to smartphone translation a few times, but were able to get a good level of detail. (I know this is a long blog post, but his farm was too interesting not to share!)

Cuong’s staple crops are:

- Rubber- Cuong has recently expanded his plantation and has many trees not old enough to tap yet.

- Bananas – we had our first ever experience of eating a banana direct from the tree – delicious! (The cutie is Cuong’s daughter, who traipsed around the whole farm tour with us).

- Wild boar – he catches adult boars in the jungle, then domesticates and breeds them, selling piglets at about 10 months old. He also has plans to use his own pig meat for his restaurant. The pigs forage for most of their feed, with supplementary sweet potato greens harvested from the banana plantation and a few pellets for the piglets.

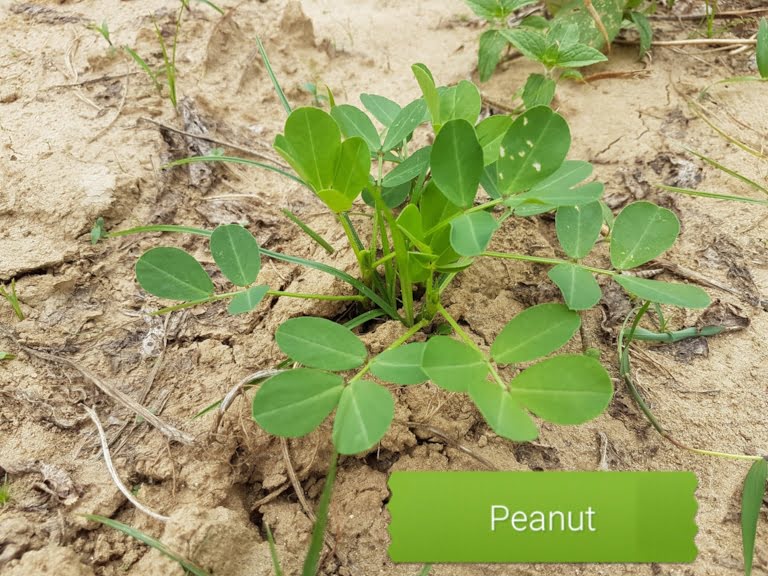

- Peanuts, which were used for the absolutely delicious peanut sauce we had with the wild boar Coung’s wife cooked for lunch;

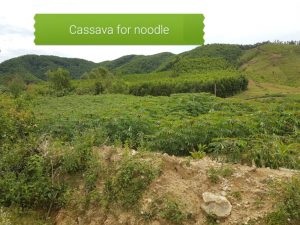

- Cassava, harvested mainly for noodles

- Sweet potato, used both for human and animal food

- Acacias, or “paper trees”, harvested for paper making. They grow quickly (the speed of growth of trees was enough to make us weep with envy), and are then coppiced and allowed to regrow.

In his move to eco-tourism Cuong’s adding all sorts of new features:

- two simple homestay accomodation rooms;

- a beautiful little restaurant (complete with hammocks) overlooking the jungle and meandering river that forms one boundary, which can be accessed for a pre-lunch swim via the stairs he’s built into the riverbank;

- an amazing tropical mixed orchard of about 100 trees including mango, “breast milk fruit tree” (a kind of sapote), papaya, lychee, jackfruit, coconut, orange and guava. He’s aiming for a big diversity of fruit to add to the farm tour and homestay experience.

There were also lots of similarities, including the constant need to be building and maintaining fences, and frustration with various pests such as wild boar eating the trunks of young trees (he was intrigued by our tales of kangaroos doing the same thing to our young apple trees!).

Cuoung and his young family work incredibly hard, for a fraction of the return on his crops that we receive, and has no control over the price he receives for many of his crops – like so many farmers the world around. Eco-tourism gives him the chance to develop his own market, set his own prices, value-add, and have a real chance to escape the cycle of poverty that so many small scale farmers experience. If you’re going to Vietnam any time soon, drop in and say g’day to him.